Standing on the roof of a continent carries weight that goes far beyond a number on a map. Altitude changes how the body behaves, how weather moves, and how small decisions echo across hours or days.

North America’s highest peaks concentrate every version of mountain risk, from arctic cold to active volcanism, from crowded trade routes to empty icefields where help sits far away. A clean elevation list tells only part of the story. Risk lives in weather patterns, terrain commitment, access to rescue, and how predictable a season tends to be.

The ranking below brings those elements together. Each peak appears with a clear Safety Risk Tier, built around objective hazards, altitude exposure, remoteness, route complexity, and regulatory signals like closures or insurance requirements.

How the Safety Ranking Works

Every mountain listed receives a Risk Tier from 1 to 5.

- Tier 1 indicates lower objective risk relative to continental giants.

- Tier 5 signals the highest objective risk based on multiple overlapping factors.

The scoring draws from five lenses that matter on real ground:

- Objective hazards such as crevasses, avalanche paths, seracs, rockfall, or volcanic activity

- Altitude exposure, including how punishing summit days and acclimatization windows tend to be

- Remoteness, measured by time to help, evacuation complexity, and communications limits

- Route complexity, covering navigation demands, technical climbing, and glacier skills

- Regulation signals, including closures, official warnings, mandatory rescue insurance, or minimum team size rules

Many of the competencies referenced here mirror the progression taught in a summit course for Mount Blanc, particularly around weather judgment, pacing, and terrain commitment.

Where published incident summaries exist, they inform the narrative context. For Denali, annual mountaineering summaries describe evacuations, injuries, and fatalities in plain terms.

For the Icefield Ranges of the Yukon, permit language and insurance requirements reveal how land managers interpret risk based on decades of response experience.

The 10 Highest Peaks in North America with safety ranking

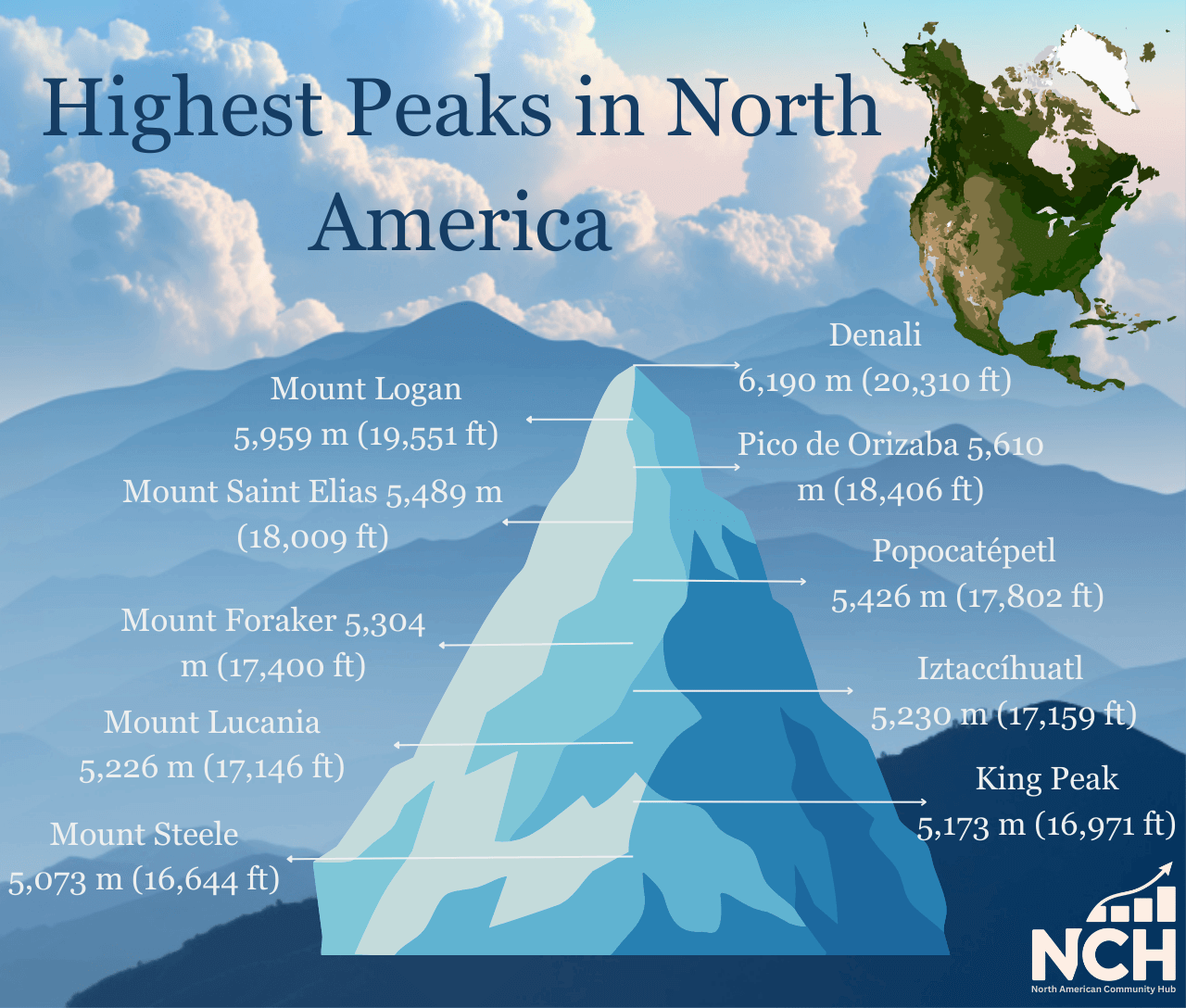

| Rank | Peak | Location | Elevation | Safety Risk Tier |

| 1 | Denali | Alaska, USA | 20,310 ft (6,190 m) | 5 |

| 2 | Mount Logan | Yukon, Canada | 5,959 m | 5 |

| 3 | Pico de Orizaba | Mexico | 18,406 ft (5,610 m) | 3 |

| 4 | Mount Saint Elias | Alaska, USA / Yukon, Canada | 5,489 m | 5 |

| 5 | Popocatépetl | Mexico | 5,426 m | 5 |

| 6 | Mount Foraker | Alaska, USA | 17,400 ft (5,304 m) | 5 |

| 7 | Iztaccíhuatl | Mexico | 17,159 ft (5,230 m) | 3 |

| 8 | Mount Lucania | Yukon, Canada | 5,226 m | 5 |

| 9 | King Peak | Yukon, Canada | 5,173 m | 4 |

| 10 | Mount Steele | Yukon, Canada | 5,073 m | 4 |

Each section below explains why a peak lands in its tier and what that means in practice.

1. Denali, Alaska, 20,310 ft, Risk Tier 5

Denali stands alone at the top of North America, and altitude only begins the conversation. Arctic cold, sustained winds, massive glaciers, and sheer scale combine into a profile that punishes impatience.

Modern measurement sets the height at 20,310 ft, and even experienced high-altitude climbers feel the difference created by latitude and cold air density.

Annual mountaineering summaries from the managing agency describe dozens of patient assessments and evacuations in a single season, along with detailed incident narratives. Rescue infrastructure exists, yet weather and altitude regularly delay aircraft and ground teams.

Practical safety notes that alter outcomes on Denali:

- Self-rescue planning matters first. Evacuations happen, though storms and thin air can stall response for days.

- Summit restraint saves lives. Many severe incidents develop during descent or while pushing through shrinking weather windows.

- Cold injury prevention deserves obsessive attention. Frostbite and hypothermia correlate strongly with rushed schedules and inadequate systems.

Denali earns Tier 5 because altitude, cold, and remoteness stack together rather than appearing in isolation.

2. Mount Logan, Yukon, 5,959 m, Risk Tier 5

Mount Logan rises from the Icefield Ranges inside Kluane National Park and Reserve and holds the title of Canada’s highest peak. Expeditions operate in a vast glaciated environment where access depends on aircraft, weather cooperation, and long timelines.

Permit requirements reveal how authorities interpret risk. Rescue insurance is mandatory, with a specified minimum coverage level. Minimum team sizes exist to reduce risk for climbers and responders alike. Typical expeditions run from 10 days to 3 weeks, and climbing seasons center on a narrow spring window.

Reasons Logan lands in Tier 5:

- Remoteness amplifies consequences. Minor injuries can escalate when help sits far away.

- Glacier exposure dominates travel. Crevasse risk persists day after day.

- Administrative rules reflect experience. Insurance and team size requirements exist because rescue carries real cost and danger.

Logan rewards strong expedition systems and punishes optimism.

3. Pico de Orizaba, Mexico, 18,406 ft, Risk Tier 3

Pico de Orizaba, also known as Citlaltépetl, rises as Mexico’s highest point and one of the tallest volcanic peaks in North America. At 5,610 m, altitude remains serious, though logistics often feel more approachable than far-north icefield giants.

Standard routes can appear straightforward during stable conditions, yet snow and glacier presence shift with the season. Access and evacuation options tend to be faster than in Alaska or the Yukon, which lowers overall consequences without removing risk.

Why Tier 3 fits Orizaba:

- Altitude still demands respect. Poor acclimatization leads to emergencies.

- Seasonal conditions redefine difficulty. Snow and ice can turn simple terrain technical quickly.

- Logistics reduce commitment. Faster access and descent options provide a safety margin.

Orizaba suits climbers building high-altitude experience while maintaining conservative planning.

4. Mount Saint Elias, Alaska and Yukon, 5,489 m, Risk Tier 5

Mount Saint Elias towers near the coast and delivers enormous vertical relief over a short horizontal distance. Storm systems roll in fast, driven by coastal weather patterns that generate high winds, heavy snowfall, and whiteout conditions.

The mountain sits inside heavily glaciated terrain, with steep faces and avalanche-prone slopes. Rescue complexity mirrors the seriousness of the environment.

Tier 5 drivers include:

- Rapid weather change that limits forecast reliability

- High objective hazard load from glaciers and steep terrain

- Severe commitment where retreat options narrow quickly

Saint Elias remains a peak for seasoned expedition teams with deep margin in skills and judgment.

5. Popocatépetl, Mexico, 5,426 m, Risk Tier 5, do not attempt

Popocatépetl ranks among Mexico’s most active volcanoes. Elevation alone never tells the story here.

Official monitoring agencies regularly publish warnings about incandescent fragments and maintain exclusion zones extending many kilometers from the crater.

Safety classification reflects official hazard messaging rather than mountaineering appeal.

Key points shaping Tier 5:

- Active volcanic behavior with unpredictable explosive events

- Formal exclusion messaging urging the public to stay away

- Unacceptable objective hazard for recreational climbing

Popocatépetl belongs on the list by height, not as a summit goal under current conditions.

6. Mount Foraker, Alaska, 17,400 ft, Risk Tier 5

Mount Foraker rises close to Denali inside the Alaska Range and shares much of its neighbor’s weather and glacial character. Despite a slightly lower elevation, Foraker demands expedition-level planning and skills.

Reasons Foraker holds Tier 5:

- Denali-range remoteness with limited rescue options

- Major glaciers and severe weather defining the route environment

- Technical competence required throughout rather than in isolated sections

Foraker does not offer a gentler alternative to Denali.

7. Iztaccíhuatl, Mexico, 17,159 ft, Risk Tier 3

Iztaccíhuatl forms a long volcanic massif near Mexico City and reaches over 5,200 m. Often perceived as less technical, the mountain still punishes complacency.

Tier 3 justification:

- High altitude exposure with cold and wind

- Route-finding challenges in poor visibility

- Rapid weather shifts are common to high volcanic terrain

Strong preparation and conservative turnaround rules reduce incident likelihood.

8. Mount Lucania, Yukon, 5,226 m, Risk Tier 5

Mount Lucania sits deep inside the Icefield Ranges and shares the same remote character that defines Mount Logan. Access often involves aircraft landings on glaciers and long traverses through crevassed terrain.

Why Tier 5 applies:

- Expedition-grade logistics required from start to finish

- Extended glacier travel increasing exposure hours

- Rescue complexity matching the most serious peaks in the region

Lucania tests systems as much as physical strength.

9. King Peak, Yukon, 5,173 m, Risk Tier 4

King Peak rises among the major summits of Kluane’s Icefield Ranges. Serious glaciated terrain and remote access dominate the experience, though crowd pressure remains low.

Tier 4 reflects:

- High objective hazards similar to other icefield peaks

- Lower traffic leading to fewer fixed-route cues

- Teams often arrive well-prepared, reducing preventable errors

Risk remains high, yet planning culture often runs strong.

10. Mount Steele, Yukon, 5,073 m, Risk Tier 4

Mount Steele rounds out the top ten and sits in the same weather and icefield system as King Peak and Lucania. Elevation clears 5,000 m, and logistics demand expedition thinking.

Tier 4 drivers include:

- Remote glaciated environment with unavoidable exposure

- Insurance and permit requirements signaling rescue difficulty

- Less notoriety compared to marquee summits, though hazards persist

Steele rewards careful logistics and conservative decision-making.

What Safe Preparation Looks Like on the Highest Peaks

Preparation determines outcomes more reliably than ambition.

Skills That Reduce Incident Likelihood

- Glacier travel and crevasse rescue practiced under stress

- Cold injury prevention for hands, feet, face, and sleep systems

- Navigation discipline using a map, a compass, and a GPS in whiteout

- Altitude plans with conservative ascent rates and clear descent triggers

Red Flags Linked to Rescues and Fatalities

- Schedules built around assumed good weather

- Teams lacking shared turnaround rules

- Minimal contingency food or fuel

- Ignoring official volcanic or weather warnings

Paperwork as a Safety Signal

Insurance requirements, team size rules, and closures exist for a reason. Land managers build policy from decades of response data. Treat permits and regulations as part of the safety system rather than administrative friction.

Closing Thoughts

North America’s highest peaks demand respect earned through preparation, humility, and patience. Elevation attracts attention, though risk lives in weather, terrain, and distance from help.

Safety ranking offers a framework for comparison, not a guarantee. Choosing objectives that match skills and systems remains the most effective safety decision available.