Egg prices in the United States have generally followed a steady upward trend since 1980, with occasional spikes due to external shocks like disease outbreaks or rising input costs.

Historically, notable surges occurred in 1984 (avian flu), 2008 (feed and fuel costs), and 2015 (H5N2 epidemic), pushing prices temporarily above $2.00 per dozen before settling.

Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, egg prices remained relatively stable, averaging $1.46 in January 2020.

However, from 2022 onward, prices began to surge in unprecedented ways. Between January 2022 and January 2023, the average price more than doubled from $1.93 to $4.82 per dozen, as noted by Fox Business.

After a brief dip, prices rose again, reaching $4.95 in January 2025 and spiking to a record $5.89 in February 2025, the highest price ever recorded, even when adjusted for inflation, according to NerdWallet.

This dramatic and sustained increase, illustrated clearly in historical pricing charts, marks an extraordinary crisis unlike any previous episode. The following sections will explore the causes behind this record-breaking price surge.

Breaking Down the 2025 Price Surge

A deadly #BirdFlu outbreak has wreaked havoc on U.S. #chicken farms, claiming the lives of over 20 million egg-laying chickens last quarter, marking the worst impact on America’s #egg supply since the outbreak began in 2022.https://t.co/TM13qGGkW6.

FarmPolicy (@FarmPolicy) January 15, 2025

Avian Flu Outbreaks Devastating Egg-Laying Hens

| The first major HPAI wave hit | Early 2022 |

| Strain responsible | H5N1 (Genotype D1.1 as of late 2024) |

| Total birds culled since the outbreak began | ~166 million poultry (by early 2025) |

| Decline in laying hen population | 9% smaller in Jan 2025 vs. three years earlier |

| Table egg production drops | 3% in 2022 – largest fall in decades |

| Production level | 5-year low of 9.1 billion dozen (USDA, 2022) |

| Price impact estimation (from HPAI alone) | ~12–24% increase in egg prices (but real prices rose much more) |

| Additional factor | Cal-Maine profits tripled (2021–2024), suggesting a possible market-driven markup |

| USDA action | $1 billion aid plan in 2025 (biosecurity, losses, vaccine trials) |

Egg prices in the U.S. have generally trended upward over the decades, but 2025 marks a historic peak. In January 1980, a dozen large Grade A eggs cost about $0.88. Prices rose gradually with inflation and periodic shocks like the 1984 spike to $1.30 after an avian flu outbreak in Pennsylvania, and the 2008 jump to $2.18 due to rising feed and fuel costs.

In 2015, another avian flu epidemic pushed prices above $2.00 again. Each time, prices eventually settled as supplies recovered. By January 2020, eggs cost around $1.46, and even the COVID-19 pandemic only caused temporary spikes, according to the Guardian article.

A dramatic shift began in 2022: prices more than doubled from $1.93 in January 2022 to $4.82 in January 2023. After dipping in mid-2023, they surged again, reaching $4.95 in January 2025. In February 2025, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a record-high $5.89 per dozen, even after adjusting for inflation.

This recent surge is unprecedented. Historical data shows prices once fluctuated between $0.75 and $2.50, but the 2022–2025 spike far exceeds past events. The next sections will examine the main causes behind this crisis.

Feed and Energy Costs Pushing Prices Up

| Key Metric | Data / Insight |

| Corn feed cost increase (2021–2022) | +18.9% |

| Soy feed cost increase (2021–2022) | +13% |

| Key global disruptions | War in Ukraine, global droughts |

| Fuel and energy costs (2022) | Reached record highs |

| Impact on wholesale egg prices | Rose 247% in 2022 (from $1.47 → $5.09 per dozen) |

| Industry quote | “Energy prices… brought up the cost of nearly everything.” |

| Trend into 2024 | Easing grain & fuel prices offered temporary relief |

| Setback | The new HPAI wave in late 2024 reversed any recovery |

Even as farmers dealt with disease outbreaks, they also faced soaring input costs. Chicken feed, mainly corn and soybean meal, became significantly more expensive in 2021–2022 due to global disruptions like the war in Ukraine and widespread droughts.

Corn and soy feed prices rose by 18.9% and 13%, respectively, from 2021 to 2022. Since feed is a major component of egg production costs, this pushed prices higher, as noted by Procurment Magazine.

Energy costs also spiked in 2022, with record-high fuel and electricity prices increasing the costs of running equipment, heating barns, and transporting eggs. These rising expenses were passed on to consumers.

By late 2022, wholesale egg prices had surged 247%, from $1.47 to $5.09 per dozen.

Although prices eased somewhat in 2023 as grain and fuel costs declined, any potential relief was offset by a new wave of avian flu in late 2024, which again restricted egg supply.

Labor Market Challenges and Wages

| Labor cost increase (2022) | Wages for low-income/agri-food workers rose ~6.8% YoY |

| Contributing factors | COVID-19 fallout, “Great Resignation.” |

| Impacts on operations | Delays in egg collection, cleaning, and processing |

| Transportation bottlenecks | Truck driver shortages affected distribution |

| COVID-era disruptions | Some processing plants shut down or cut capacity |

| Improvement trend (2023–2024) | Unemployment declined; the workforce began stabilizing |

| Labor-related price contribution | Added a few % to final egg prices |

| Labor strikes | Indirect impact: eggs are not as affected as other food sectors |

Labor market challenges have also contributed to rising egg prices. The COVID-19 pandemic and the “Great Resignation” led to labor shortages across egg farms and processing plants, reducing the workforce available to collect, package, and distribute eggs.

At the same time, certain sectors, like technology and healthcare, saw rapid growth, drawing workers away from industries like agriculture and food processing.

By 2022, wages for lower-income workers, such as those in agriculture and food processing by about 6.8% year-over-year.

Producers often had to increase pay or offer bonuses to retain staff, raising production costs.

Labor shortages also caused operational delays, like missed egg collection or sanitation, and trucking bottlenecks further disrupted supply chains. Some processing plants even reduced capacity or temporarily shut down during peak labor shortages.

While the situation improved somewhat in 2023 and 2024, wages remained higher than pre-pandemic levels.

Labor union actions in the broader food sector added additional strain, though eggs were less directly affected. Overall, labor has been a secondary but notable factor in egg price inflation, compounding the effects of feed costs and disease outbreaks.

Supply Chain Disruptions and Regulatory Factors

| Packaging shortages (2021–22) | Cardboard/foam cartons became more expensive and scarce |

| Transportation costs | The diesel fuel surge increased trucking expenses |

| Regional disruptions | Rail shortages, storms (e.g., Midwest blizzards), delayed egg deliveries |

| California Proposition 12 (2022) | Required cage-free eggs; removed some suppliers, pushed West Coast prices up $1–2 |

| Other state regulations | Similar cage-free mandates phased in; slight short-term drop in productivity |

| U.S. egg exports (2022) | Fell 52% (161M dozen, down from 335M in 2021) due to bans and domestic priority |

| U.S. egg imports (2023–2025) | Imports from Brazil nearly doubled in early 2025 |

| EU egg import efforts | U.S. sought eggs from Spain & Poland, but regulatory differences limited supply |

| Effect | Modest boost to domestic supply, but not enough to offset production decline |

Egg prices were pushed higher by a cascade of supply chain problems and regulatory factors. Shortages of packaging, higher diesel costs, and weather-related transport delays raised the logistical cost of getting eggs to market.

The cage-free mandate in California removed some non-compliant producers from the supply chain, raising prices on the West Coast. Nationally, cage-free transitions caused slight dips in output.

View this post on Instagram

On the trade side, U.S. egg exports dropped sharply in 2022, while imports from Brazil and Europe increased but were limited by health and regulatory barriers. While these steps helped a little, they couldn’t compensate for the scale of supply loss from avian flu.

Demand Shifts and Consumer Behavior

| Long-term demand trend | Upward since the 2000s; ~291.6 eggs per capita in 2019 |

| Per capita consumption (2022) | ~277 eggs/person, despite shortages |

| Pandemic effect (2020) | Small dip due to restaurant closures, then home-cooking rebound |

| Inflation behavior | Eggs substituted for pricier proteins → kept demand high even as prices rose |

| Seasonal spikes | Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter increased demand during flu-driven shortages |

| 2023 demand softening | Some buyers began cutting back or substituting (e.g., egg replacers) |

| Price elasticity | Low-income consumers still bought eggs at high prices |

| Industry consolidation | Few large firms control supply; potential for market-driven “excuseflation.” |

| Price gouging concerns | Reports of record profits despite modest production dips (e.g., Cal-Maine) |

Despite record-high prices, demand for eggs remained surprisingly strong. Americans’ egg consumption had been rising for years, and during periods of broader food inflation, many consumers turned to eggs as a relatively affordable protein.

Holiday demand spikes further tighten supply.

Though 2023 saw early signs of buyers cutting back, demand remained relatively inelastic. Meanwhile, the industry’s consolidation with a few large players controlling most supply, raised concerns about price manipulation.

Some watchdogs argued that price increases exceeded actual cost hikes, boosting profits while hurting consumers.

Cost Pressures on Baked Goods and Food Manufacturing

Eggs play a vital role in many food products: breads, cakes, cookies, mayonnaise, custards, sauces, pasta, and more.

As egg prices spiked, restaurants, small bakeries, and large manufacturers all faced rising input costs, forcing them to raise prices, change recipes, or cut offerings altogether.

Egg-Dependent Products Affected by Price Surge

| Baked goods (bread, pastries) | Ingredient costs surged, leading to retail price hikes and smaller margins |

| Sauces & dressings (e.g., mayo) | Some brands lowered egg content or swapped in powdered egg alternatives |

| Processed foods (e.g., pasta, cake mix) | Manufacturers reformulated recipes to reduce egg use |

| Café & restaurant items | Items like egg coffee, kaya toast, and omelets were removed or made pricier |

| School/institutional menus | Protein alternatives added to reduce reliance on expensive eggs |

For example:

- A New Orleans bakery reported that the cost to make its popular King Cakes for Mardi Gras rose significantly due to $5+ per dozen egg prices, according to AP News.

- In San Francisco, a well-known café removed egg coffee from its menu, as fresh yolks became too expensive to justify in a niche drink.

- Waffle House and Denny’s began adding $0.50–$1 surcharges on breakfast plates containing eggssomething unheard of before this crisis.

Wholesale Volatility and Ingredient Hoarding

The wholesale market for eggs has experienced wild swings in pricing, making it difficult for food businesses to plan.

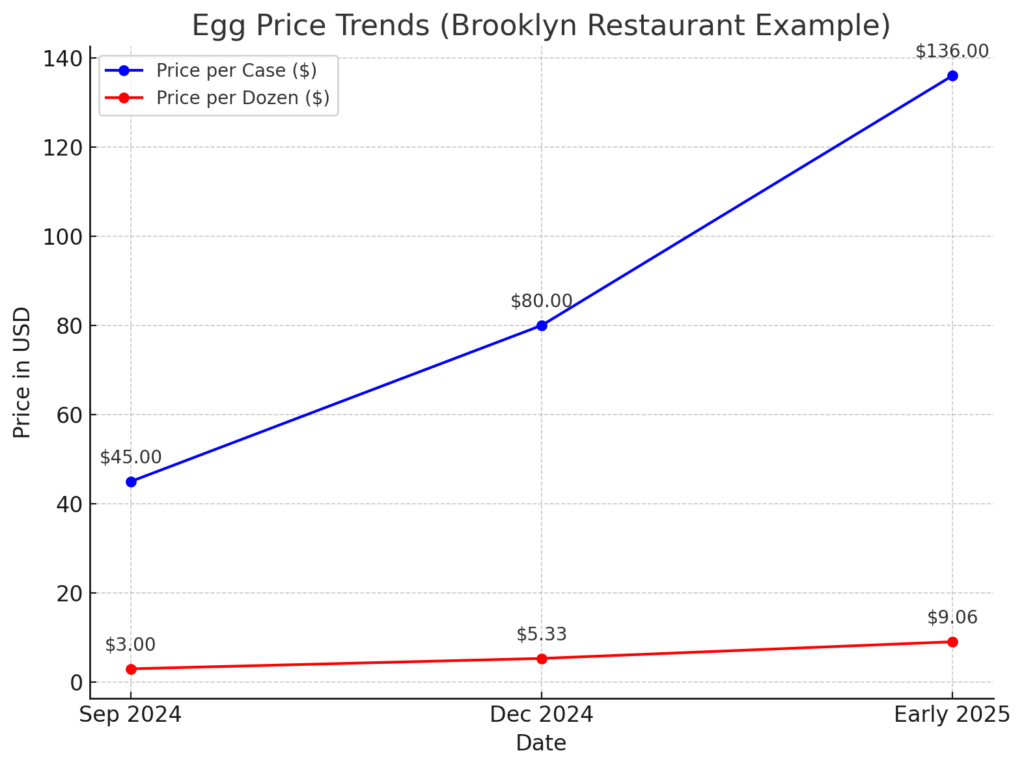

Case Egg Price (15 Dozen Loose Eggs) – Brooklyn Restaurant Example

One Brooklyn restaurant owner said, “I’ve never seen prices increase this quickly.” Initially, he avoided raising menu prices but eventually had no choice.

Another bakery owner stockpiled eggs in advance of an expected spike, turning extra fridge space into emergency inventory.

Fast food chains also responded: some limited-time breakfast offers were pulled, and menu prices quietly adjusted upward. Schools and institutions revised menus to include lower-cost protein alternatives, especially in breakfast items.

CPI Movement in Egg-Heavy Categories (Selected, 2023)

| Category | Approx. Increase | Primary Drivers |

| Bread & Bakery Products | +6–9% | Eggs, flour, energy |

| Processed Mixes (cake, pancake) | +5–8% | Egg and milk-based ingredients |

| Mayonnaise & Dressings | +4–7% | Egg yolks, vegetable oils |

| Fast-Food Breakfast Menus | +10–15% (regionally) | Egg surcharges, supply chain costs |

Even after meat and dairy prices began to stabilize, eggs continued driving food inflation through the start of 2025.

Analysts estimate that egg inflation alone contributed 1.5–2 percentage points to overall grocery inflation between 2022 and 2024, according to CNN.

Lifestyle Changes and Retail Trends (2024–2025)

| Store limits on egg cartons | Retailers began rationing: “2 cartons per customer” during peak shortages |

| Egg thefts | Some stores saw increased shoplifting of eggs, similar to high-end meats |

| Security protocols | Eggs were moved to more visible shelves or required staff to unlock access |

| Consumer substitution | Home cooks turned to applesauce, flaxseed, or boxed mixes to replace eggs |

| Menu changes | Egg-heavy dishes removed, replaced, or subject to price markups |

Consumers began treating eggs as a specialty item, not a staple. For some, the increase meant less baking at home, or skipping recipes like custards or soufflés entirely.

Others adjusted by stretching recipes, using egg substitutes, or turning to more plant-based breakfast options.

International Comparisons – Egg Prices in 2025 Around the World

Egg prices have been climbing not just in the United States but in many countries, though the severity and causes vary.

In 2025, some nations are also struggling with high egg costs, while others have been more insulated. Here we’ll compare the U.S. experience with that of Europe, Canada, and other OECD countries.

Europe – High Prices, But Improving Supply

Europe faced its own bird flu outbreaks and inflationary pressures, leading to significantly higher egg prices in 2022 and 2023. The European Union saw an egg price increase of about 30% from January 2022 to January 2023 on average, according to Eurostat data.

This was driven by many of the same factors as in the U.S.: avian influenza culls in countries like France, the UK, and Italy, as well as surging feed and energy costs (exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, which affected grain and fuel prices in Europe).

By late 2022, consumers in Europe were paying considerably more for eggs than a year prior, and some supermarkets in Britain even rationed eggs during the worst of the shortage.

However, as of early 2024, Europe’s situation was stabilizing a bit. Egg prices in Europe were 10–15% lower in early 2024 than a year before, according to industry analysis, but still about double their 2021 levels.

In practical terms, that means if a dozen eggs cost €2 in 2021, they might have been around €4 at the 2023 peak, and perhaps around €3.50 in early 2024.

European consumers felt the pinch, but not to the extent of U.S. consumers, who endured a 100%+ increase.

By 2025, some European countries had increased their egg production (the EU overall registered a small production rise in 2024 over 2023), which helped temper prices.

The EU also has substantial government support and market interventions – for example, financial aid to poultry farmers hit by avian flu, and strategic trade adjustments. When certain countries (like France) were short on eggs, others (like Spain or Poland) could often fill the gap, thanks to the EU’s single market facilitating intra-Europe trade.

One interesting difference is that Europe’s production system has more small and medium farms (and more free-range flocks). This meant avian flu, while still deadly, sometimes had a less catastrophic effect on national supply than in the U.S., where a single farm losing 1 million hens has a big impact, as noted by Global Health.

Europe certainly had its losses – France had to cull over 10 million birds in one outbreak, and Italy and Poland each lost millions – but by 2024, the EU overall laying hen flock was rebounding.

Also, European consumers were somewhat cushioned by the fact that eggs were already a bit more expensive (and in many places, sold by different grades) to begin with, and European diets rely slightly less on eggs (per capita consumption in the EU is lower than in the U.S.).

That said, by 2025, European egg prices remained high by historical standards. For example, in Germany, a dozen eggs that cost about €1.70 in 2020 cost around €3.00 in 2025. In the UK, a half-dozen eggs that might have been £1 are now closer to £1.80–£2.00. European farmers also face higher costs from new animal welfare rules and lingering feed cost issues.

So, Europeans are not escaping the egg inflation – they just didn’t see the crazy quintupled prices that some U.S. shoppers saw at the peak. Notably, Europe was also approached by the U.S. to export eggs to help America’s shortage in 2025, but Europe didn’t have much to spare.

With Easter approaching in spring 2025, European producers were focused on their own markets and also hampered by the fact that U.S. egg safety regulations (requiring washing and refrigeration) conflict with European standards (which prohibit washing eggs and keep them unrefrigerated on store shelves).

Canada – Steady Supply Through a Different System

View this post on Instagram

Canada’s experience with egg prices has been markedly different from the U.S. despite facing the same avian flu virus. Canadian consumers did see egg prices rise, but nowhere near the extent in the U.S. In early 2023, as U.S. prices jumped 60–100% year-over-year, Canadian egg prices were up only about 11–12% on average, according to retail-insider.com

By 2025, Canadians will find a dozen large eggs for around CAD $4.50–$5.00 (Canadian dollars), which is roughly USD $3.50–$3.75 – not cheap, but relatively moderate compared to U.S. prices that were often $5–$6 (or more) at the same time, according to NPR.

In fact, Americans have generally been surprised to learn that eggs, which used to be cheaper in the U.S. than in Canada, flipped to being much more expensive in the U.S. in 2023–2024.

Why the difference? The answer lies in Canada’s supply management system and farm structure. Canada regulates its poultry and egg industry with a quota system – production is tightly controlled to match domestic demand, and prices are set to ensure farmers cover costs.

This system prioritizes stability over rock-bottom prices. In normal times, Canadians pay a bit more for eggs than Americans (because Canadian farmers are guaranteed a minimum price), but in bad times, Canadians avoid the extreme volatility.

When avian flu hit, Canada’s egg farms, which are generally smaller and more geographically dispersed, were less vulnerable to nationwide collapse. A Canadian farm on average has about 25,000 hens, versus many U.S. farms with over a million hens in one site.

Thus, an outbreak on one Canadian farm wipes out fewer birds (and a smaller percentage of national production) than an outbreak on a U.S. mega-farm. Indeed, Canada did suffer losses – over 14.5 million birds were culled in the HPAI outbreak (mostly in one hard-hit province, British Columbia)

However, the Canadian system was able to compensate by shifting production from other regions. For example, Alberta shipped eggs to B.C. to cover the shortfall

Moreover, because the Canadian Egg Marketing Agency (known as Egg Farmers of Canada) adjusts prices periodically based on feed costs, etc., Canadian egg prices crept up modestly rather than spiking overnight.

Economists note that Canada’s tightly regulated market acted as a buffer. As one Canadian economist pointed out, “We have not had any shortage of eggs… that’s in the U.S., it’s not happening here,” emphasizing that Canadian stores remained well-stocked

Egg Price Increases and Consumption

| Rank | Country | Egg Price (USD/dozen) |

| 1 | New Zealand | 6.52 |

| 2 | Switzerland | 5.90 |

| 3 | Norway | 5.71 |

| 4 | Uruguay | 5.48 |

| 5 | Puerto Rico | 5.00 |

| 6 | Bulgaria | 4.98 |

| 7 | Australia | 4.92 |

| 8 | Sweden | 4.79 |

| 9 | South Korea | 4.54 |

| 10 | Germany | 4.54 |

| 11 | USA | 4.40 |

| 12 | Belgium | 4.22 |

| 13 | Ireland | 4.22 |

| 14 | UK | 4.14 |

| 15 | Denmark | 4.06 |

| 16 | France | 4.00 |

| 17 | Austria | 3.90 |

| 18 | Czechia | 3.90 |

| 19 | Slovakia | 3.90 |

| 20 | Hong Kong | 3.85 |

| 21 | Japan | 3.84 |

| 22 | Chile | 3.77 |

| 23 | Serbia | 3.64 |

| 24 | Romania | 3.63 |

| 25 | Finland | 3.57 |

| 26 | Israel | 3.51 |

| 27 | Italy | 3.46 |

| 28 | Morocco | 3.37 |

| 29 | Greece | 3.35 |

| 30 | Latvia | 3.35 |

| 31 | Lithuania | 3.25 |

| 32 | Croatia | 3.14 |

| 33 | Poland | 3.11 |

| 34 | Ghana | 3.03 |

| 35 | Hungary | 2.90 |

| 36 | South Africa | 2.89 |

| 37 | Netherlands | 2.81 |

| 38 | Canada | 2.73 |

| 39 | Costa Rica | 2.64 |

| 40 | Colombia | 2.60 |

| 41 | Portugal | 2.60 |

| 42 | Slovenia | 2.60 |

| 43 | UAE | 2.56 |

| 44 | Jordan | 2.54 |

| 45 | Singapore | 2.54 |

| 46 | Ivory Coast | 2.50 |

| 47 | Mexico | 2.45 |

| 48 | Thailand | 2.44 |

| 49 | Kenya | 2.43 |

| 50 | Tanzania | 2.42 |

| 51 | Peru | 2.41 |

| 52 | Spain | 2.38 |

| 53 | Nigeria | 2.37 |

| 54 | Ukraine | 2.34 |

| 55 | Malaysia | 2.32 |

| 56 | Ecuador | 2.30 |

| 57 | Kuwait | 2.27 |

| 58 | Philippines | 2.23 |

| 59 | Vietnam | 2.16 |

| 60 | China | 2.15 |

| 61 | Saudi Arabia | 2.13 |

| 62 | Tunisia | 2.09 |

| 63 | Sri Lanka | 2.03 |

| 64 | Guatemala | 2.02 |

| 65 | Uganda | 2.02 |

| 66 | Azerbaijan | 2.00 |

| 67 | Cameroon | 1.97 |

| 68 | Brazil | 1.93 |

| 69 | Turkey | 1.89 |

| 70 | Bolivia | 1.87 |

| 71 | Dominican Rep. | 1.82 |

| 72 | Kazakhstan | 1.69 |

| 73 | Indonesia | 1.65 |

| 74 | India | 1.64 |

| 75 | Paraguay | 1.62 |

| 76 | Pakistan | 1.53 |

| 77 | Egypt | 1.52 |

| 78 | Russia | 1.27 |

| 79 | Zambia | 1.24 |

| 80 | Bangladesh | 1.23 |

Final Thoughts

In 2025, eggsonce among the cheapest staples in the American kitchenhave become a symbol of how fragile food systems can be. The primary driver of this price surge was a relentless avian flu outbreak that decimated laying hen flocks, but it was worsened by soaring feed and energy costs, labor shortages, and supply chain disruptions.

Together, these factors pushed egg prices to historic highs, reshaping everything from restaurant menus to breakfast habits.

This crisis has revealed deep contrasts in how food systems handle shocks: while the U.S. struggled under its free-market model, Canada’s supply-managed approach and Europe’s policy tools helped maintain greater price stability.

It’s also sparked unusual trends from egg smuggling to backyard chicken rentals and serious discussions about food security, corporate behavior, and disease resilience.

Looking forward, there’s cautious optimism. Feed prices are easing, and the USDA expects egg production to rebound. If bird flu is brought under control, prices could fall closer to pre-2022 levels, though likely not all the way back.

For now, the egg crisis has left a lasting mark, showing how even simple, everyday food can be dramatically affected when nature, economics, and policy collide.

As one farmer reflected: “You never knew when you woke up whether your flock was healthy or not.” That uncertainty is now shared by consumers, grocers, and policymakers, reminding us just how vulnerable the food chain really is.